THE ETHICS OF WOOD

Interview with Formafantasma

When did you start thinking about the theme of sustainable design?

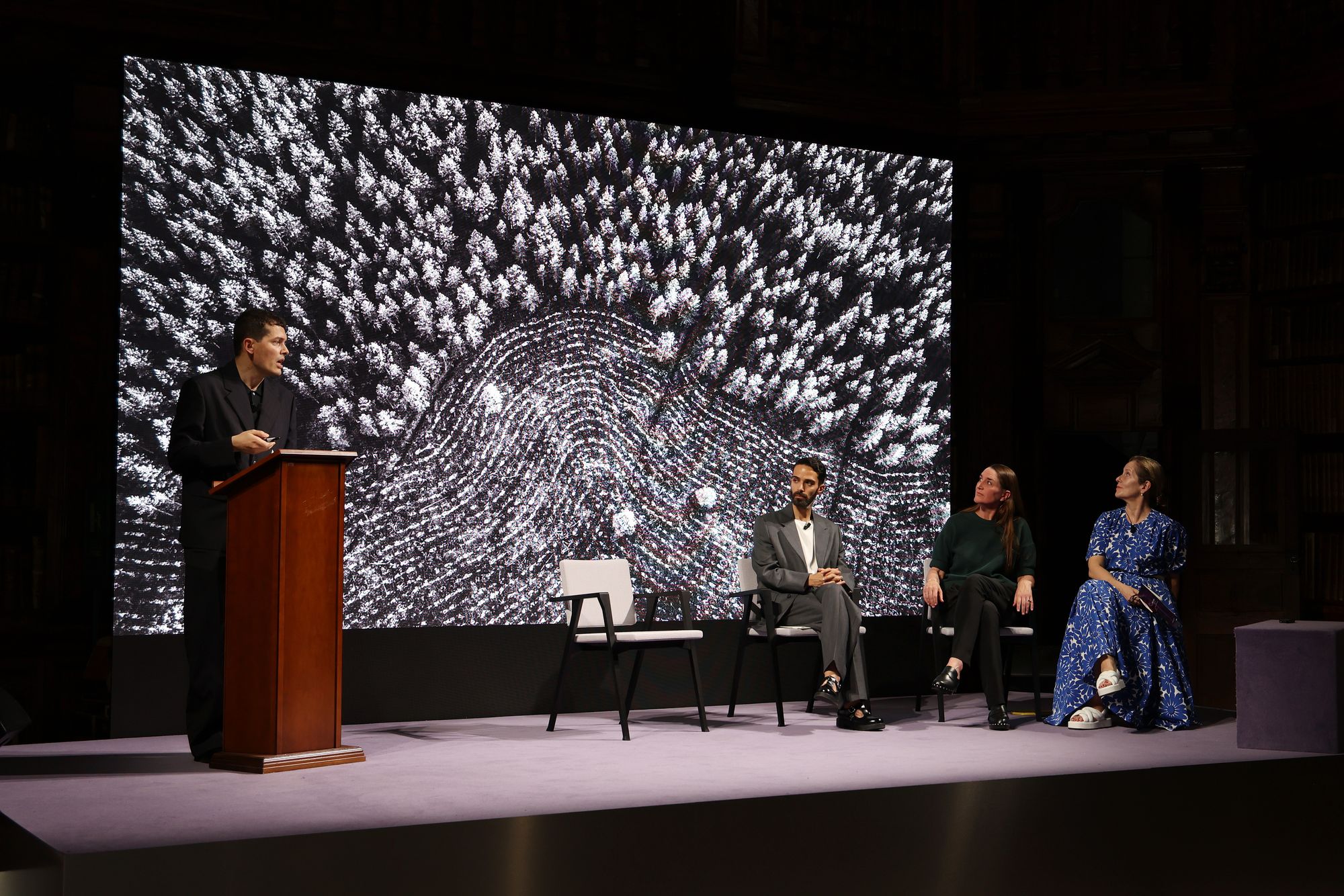

We began to deal with this issue before the pandemic because Miuccia Prada had invited us to do a project related to education. Reflecting on the project we understood that we didn’t want only to address students so the idea of a symposium for a wider audience was therefore born, its purpose being not so much to present products but a way of going deeper into cultural and ethical questions.

So this is how the “Prada Frames” symposium was born?

Exactly. The first edition took place during the Salone del Mobile in Milan last June during which we wanted to focus on a theme that’s very important to us in the context of design, that of the forest and timber extraction. Our idea was to look beyond the product, to explore the impact of the industry and consider the forest from an ethical point of view. We mustn’t forgot that forests are inhabited by different animal species of course, but also by indigenous communities and

therefore it needs to be a reflection that goes beyond design and takes on environmental and also political significance.

How did you structure the symposium?

We chose to keep an academic tone by alternating short keynotes with multidisciplinary conversations. Among the speakers were creatives, architects, designers, artists but also anthropologists and philosophers. We talked about forest governance and carbon offsetting, looking at the issues in a critical way and also trying to resolve the question of economic conflicts.

What conclusions did you come to?

In a symposium of this kind one does not reach conclusions, it is rather a research project in which we tried to frame the issue and glean ideas or pointers that we can apply in our research projects. Let me explain. Our studio is made up of two parts, one dedicated to research and the other a more “commercial” arm. The first works on long-term research projects that result in publications, symposia such as the Prada one or exhibitions such as “Cambio” at the Serpentine in 2020, which was also dedicated to the theme of wood in design and the extractive nature of the timber industry (the exhibition was subsequently shown at the Pecci Center in Prato and at the Museum für Gestaltung in Zurich). As part of our more “commercial” work we then try to apply the results of this research, to a greater or lesser extent, in the projects we do with some of our clients.

Can you give us some examples?

Of course, the project we are working on with Artek is one example. After seeing our exhibition at the Serpentine and learning about our approach to wood, the most important raw material in the production of Artek furniture, the company invited us to work on a project and gave us free rein to their supply chain. Artek is a very particular case because it is one of the few companies with a short supply chain It’s a historic company that operates according to sustainable ecological

development principles in the sense that it uses a particular type of wood - birch that it extracts 250 kms from its sawmill in Finland.

So we joined forces with the company for six months and observed its production processes, making suggestions and developing a few of these, such as 82 rethinking some of the details of the iconic Alvar Aalto stool.

In what way did you rethink it?

Typically birch wood has knots on its surface but today more and more often it also carries marks left by insects that have moved northwards with the warming climate, settling in the forests. Until now Artek would try to discard any wooden pieces that bore these marks or knots and reserve them for the production of paper. Paper, however, is not as long-lasting a material as a piece of furniture, so we tried to implement these characteristics in the wood of the stool. To do this,

however, we first need to re-educate the customer who must learn to accept the fact that wood is a living material. For this reason the presentation of the product must be linked directly to climate change and contribute to raising public awareness.

It is important to make the customer understand that the quality of the product hasn’t changed, but that if they can accept the peculiarities of this wood, fewer trees will be discarded.

Let’s talk about exhibition design

Another part of our studio is dedicated to exhibition design. We created the Bernini and Caravaggio exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in 2020, part of the exhibition design for “The Milk of Dreams” at this year’s Venice Biennale and the Fondation Cartier exhibition at Milan’s Triennale, also this year, entitled “Real World”. The latter is a good example of the issues we are tackling. In fact, in dialogue with the director Hervé Chandès, we created an installation that followed

a very pragmatic approach, even if the final impact is nevertheless sophisticated.

Specifically, we kept the existing walls where we could and didn’t change their colour. This may seem a trivial detail but in reality a lot of paint would have been required and white is the easiest colour to adapt to future exhibitions, or in any case it works well as a base for other colours. To create the dividing walls in the spaces reserved for videos, which we usually try to separate, we chose to create ephemeral dividers using vertically suspended A3 sheets of paper. To create

the cinema room on the other hand, we collaborated with a Milanese company called Spazio Meta, which salvages materials that can then be reused for sets and exhibition designs, and borrowed some carpets. We did the same with the Tacchini design company, which lent us objects that will be returned to the company.

So, on the one hand we worked on the material, on the other on strategic questions, so we were able to create an installation out of very few elements.

Let’s talk about “Cambio”, the Serpentine exhibition?

The idea was born two and a half years ago when Hans Ulrich Obrist asked us to create a manifesto exhibition. Since the Serpentine is located inside Hyde Park we decided to dedicate an exhibition to the governance of the timber industry.

In this case too we didn’t ask the designers to talk about the functional and aesthetic characteristics of the wood in the product but we wanted rather to ignite an awareness about the extractive nature of the industry. As with Prada, we involved a number of experts, scientists but also an indigenous community from the Colombian Amazon. Together with a consultant from the European Union we analyzed how wood imports into Europe work, also investigating how illegal extraction manages to overcome the restrictions set by the European community, which in any case were only introduced about 10 years ago. We started with a series of everyday objects, which we analyzed with the Thünen Institute that researches wood anatomy, to understand which items contained illegally extracted wood. For example, you can find protected Brazilian woods hidden inside barbecue charcoal, which are not easy to recognize since they are burned and therefore manage to evade checks.

What are your future projects in this area?

We are working on many projects, but one in particular is interesting in this context. It’s a project for the National Art Gallery in Norway and will be presented in the spring of 2023. It focuses on wool production, a theme that was commissioned but which is very dear to our hearts, above all in terms of the connection with the animal. We are focusing on the complex relationship with living beings in the context of the wool industry, whose production monopoly lies in Australia, and also on comparisons between the industry and sheep farming in countries such as Italy, where the former is now practically disappearing.

What general direction is your practice going in?

On the one hand it’s becoming more commercial through consulting projects with brands such as Prada, on the other we are going more in-depth with the research aspect, which does not have the creation of a product as its goal but rather the production of knowledge, publications or exhibitions. This research flows, as I said, into our products. For example, in the light of our research into wool we

are rethinking upholstery products, which mainly use mainly synthetic materials today. In this context we are trying to think about how to recover and reuse wool, thus solving the problem of maintenance over time.

And is the industry moving towards a greater awareness?

All companies are trying to be more sustainable, but many don’t know how as they are relatively small in scale so don’t have the resources internally and don’t have a dedicated sustainability department.

The real problem is that we need to build an ecological culture. It doesn’t matter if the impact is limited, it is necessary to do it anyway. Many people don’t know how to develop ecological thinking, they use a technocratic approach and call on others to apply directives. Instead it is necessary to develop a culture and that takes more than one generation. But we don’t have that much time. The problem, then, is that if the economic system is based only on development there will never be ecological change. In fact, despite our efforts, emissions have increased, therefore either a philosophical rethink is implemented or there is no way out.

Formafantasma is a design studio founded in 2009 by Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin based on research that investigates the ecological, historical, political and social forces that shape the discipline of design today. Working from their studio in Milan (Italy) and Rotterdam (Netherlands), the studio spans a broad spectrum of typologies and methods, from product design to spatial design, strategic planning and design consultancy. Formafantasma is an award-winning studio, including: 2021 Wallpaper * Awards Designers of the Year / Winner, 2020 Dezeen Designer of the Year / Winner, 2019 Milano Design Award / Winner, 2019 Beazley Designs of the Year / Nomination. In March 2020 the Serpentine Galleries dedicated a personal exhibition to Formafantasma and their in-depth investigation into the governance of the wood industry.